Where is the infinite apparent?

A sustained note in the dark? A small gesture learnt and repeated? Is it experienced in an instant, or in the durational–all at once or for all time?

One Infinity is a collaboration between choreographer Gideon Obarzanek and composers Wang Peng, Max De Wardener and Australian recorder virtuoso Genevieve Lacey, alongside Jun Tian Fang music ensemble, Beijing Dance Theatre and Townsville-based dance company Dancenorth. There is, as this lengthy list of collaborators suggests, a lot going on here. But the numerous perspectives and mediums involved in the project serve the concept behind the work’s title: this is ultimately a piece that explores the interplay between singularity and multiplicity, unification and diversity. Through a more pragmatic sense, it is a work that attempts to strike evocative equilibrium between dance, sound, music, movement and performance. In a panel discussion at the Wheeler Centre, Obarzanek suggested that One Infinity is a music recital where dance serves to visualise the listening experience. Though this might be the case, no aspect of the performance cedes centrality to another. Which is why we, the audience, are called upon to actively contribute to the manifestation of the work.

We sit on stepped seating either side of a narrow stage at Melbourne’s Malthouse Theatre. Casually, Obarzanek and the show’s producer enter and explain, in both Mandarin and English, that before the performance begins, we must take part in a lesson. They then instruct the two sides of the audience to emulate the movements of their respective leaders, perched like deities atop each set of bleachers. We follow along, raise our hands, cross them at the wrists, and float them back down onto our laps to rest a little more tensely than before, anticipating the possibility that we might again be called upon to raise them.

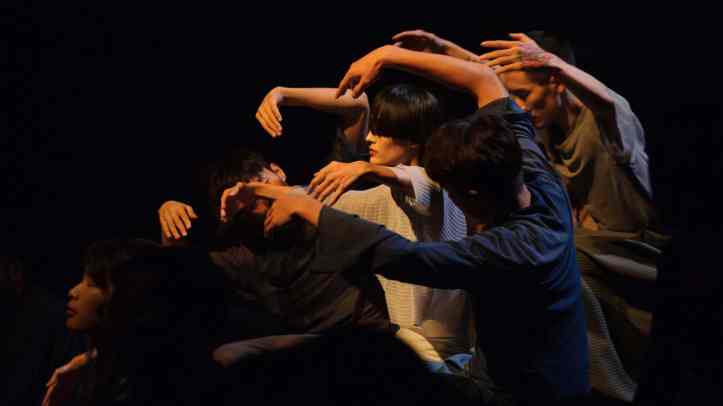

This tension is then absorbed into the performance, as the lights dim and Lacey, seated on the stage, builds the solitary warble of her recorder into an increasingly complex melody. Because of the staging, and because I’ve come to this piece under the assumption that it is, primarily, a dance work, the physicality that produces the sound seems particularly pronounced. I watch as Lacey’s fingers move to cover the holes of her instrument in order to alter the sound it emits, and I think about how this process of obfuscation creates the variation that constitutes the piece’s whole. This practice is mirrored in the choreography as, early in the piece, the light falls on a group of dancers seated amongst the crowd on the opposite set of bleachers. They perform a series of contractions, to then unfurl like petals in bloom. I first witness this from a distance, unobstructed, only to later view the same sequence repeated by dancers who rise from the seats directly in front of me. In the latter instance, my proximity to the performers sees that I’m unable to observe the phrase in its entirety. Instead my experience is noticeably individualised and I become literally and acutely aware of my own place within the whole.

Through the physicality of its undulating movement, One Infinity seems conceptually to sway between these moments of contracted focus, and an expansive sense of immensity. The latter is evoked aurally and visually through the musical components of the performance. There is a profound feeling of continuity that emanates from the use of traditional Chinese instruments including various woodwind instruments, played by Xiao Gang, and three guqins played by Zhang Lu, Wang Peng and Zhuo Ran. Centuries of practice and mastery reverberate from the small acts of plucking and sliding, and the distinctive twang that the guqins produce. In integrating these instruments and their associated repertoire into One Infinity, the artists give form to the ways in which time, and history, move continuously through things.

While the bulk of the performance consists of pieces from the guqin repertoire, played in their entirety, there are also a number of contemporary interspersions that populate the soundscape. These take the form of compositions that Lacey performs on various recorders, and a backing track that fills out moments when the live musical components recede. The capacity for movement to facilitate engagement–with others, objects, and the past as it appears in the present–is illustrated effectively by both the live music and choreography. Both disciplines are underscored by the durational, and in both cases, we see or experience the product of their score as it moves through the body, our bodies. In this regard, the backing track feels comparatively disengaged–a mesh of distortion that enters the work from on high, seemingly to the contrary of the piece’s other elements that are drawn, in the immediate, out of visible physical interaction.

The inter-disciplinary territory traversed in One Infinity has become something of a trademark of Obarzanek’s work. Such an approach was deployed to mesmerising effect in 2017’s Attractor, which Obarzanek co-choreographed with Lucy Guerin. Like One Infinity, Attractor sees musicians share the space with dancers in a manner that imbues the music with a physicality often obscured in contemporary dance works. Yet unlike in One Infinity, Attractor seeks to progressively blur the material distinctions between musician and dancer. In this earlier work, members of Indonesian metal duo Senyawa are alternately the manipulated and manipulators–at times invoking in the dancers what look like the symptoms of ritualistic possession, while at others submitting to the literal pull of the movement, as dancers drag the still-playing musicians around the space. One Infinity lacks this synthesis because it is, as its title suggests, about the individual’s relationship to the whole. There then necessarily needs to be a sense that each aspect of the performance is distinct, and that these distinctions are as much a part of the work’s totality as the roles they define. In this way, One Infinity lacks the anarchic sense of continual transference and transformation that made Attractor feel urgent and unpredictable. Instead, from my position on the bleachers, it feels like a slow, inevitable unfolding, wherein the element of revelation is overcome by both the understanding that everyone will play their assigned part, and the innate desire to predict when I might be called upon to perform mine.

Yet the shortcomings of One Infinity are perhaps inescapable given the subject matter. Any attempt to encompass the infinite within the finite is going to feel fragmentary. A finite structure simply cannot capture fully something that is by definition unimaginably vast. It is then, the piece’s surrender to, and experimentation with, this fact, that is its most admirable attribute. The piece begins with a singular focus on Lacey’s solitary recorder. By its conclusion the emphasis is drawn to opposing ends of the stage, with Lacey standing, playing long, low notes on a large woodwind instrument as she faces Wang Peng and the eerie slide of his guqin. From one point, to many, and then just to two. Here the infinite is not so much present, but gestured toward, as it moves through bodies, echoed by things, that in their association and variation constitute the whole.

One Infinity

Malthouse Theatre

October 2018

Elyssia Bugg is a writer and critic based in Melbourne. She is fascinated by performance and the performative. Her writing on these topics has previously appeared in RealTime Magazine.